Japanese encephalitis is a challenging condition to diagnose, especially in its early stages when symptoms are vague and often resemble other common infections. As a viral disease that targets the brain, it needs quick and accurate diagnosis. This can help improve outcomes and reduce the risk of long-term brain damage. Doctors rely on clinical signs, a history of exposure, and lab tests to identify the virus. Diagnosis can be complex, especially in areas with limited resources. But early detection is vital for patient care and public health planning.

There is no cure for Japanese encephalitis. So, the main goal of diagnosis is to confirm the illness, rule out similar diseases, and begin supportive treatment. It also helps track outbreaks and guide vaccine efforts in high-risk areas.

Clinical Symptoms and Early Clues

The first step in diagnosing Japanese encephalitis is a thorough clinical check. Doctors assess the patient’s symptoms, such as high fever, headache, confusion, seizures, and nerve problems. These signs often get worse over a few days. If coma or paralysis sets in, doctors suspect a serious brain infection.

However, many other illnesses can look similar. Malaria, meningitis, and other viral infections can cause the same symptoms. So, Japanese encephalitis is usually a diagnosis of exclusion, especially in regions with many infectious diseases.

A recent stay in rural or mosquito-prone areas can provide a strong clue. In children, sudden seizures and confusion without injury should raise concern.

Role of Exposure and Travel History

Doctors must review the patient’s exposure history to assess the risk of infection. These questions are key:

- Has the patient been to a country in Asia or the Western Pacific?

- Did the trip happen during the rainy or mosquito season?

- Did they stay near rice fields or farms, especially where pigs are kept?

- Have they been vaccinated against Japanese encephalitis?

These details help doctors decide whether testing is needed. In areas where the virus is common, all unexplained brain infections should be checked for Japanese encephalitis—especially in people who are unvaccinated.

Testing for Japanese Encephalitis

Lab tests are essential for diagnosis. The most used test is called MAC-ELISA, which looks for IgM antibodies in the blood or spinal fluid. These antibodies appear 4–8 days after symptoms begin and peak in the second week.

MAC-ELISA is:

- Highly sensitive when done properly

- Common in countries where the virus is present

- Able to provide quick results

But it also has limits:

- Results can be false-positive if the person had other flaviviruses like dengue

- It may miss early infections and need a second test

- It may not be available in rural clinics

So, test results must be considered along with clinical signs and exposure history.

Other Tests and Imaging

PCR testing can detect the virus’s genetic material in blood or spinal fluid. It works best early in the illness, before symptoms of brain infection appear. PCR is accurate but costly and often only found in research labs or major cities.

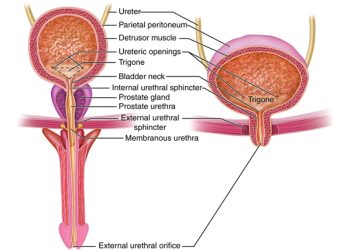

Doctors may also perform a lumbar puncture to check the spinal fluid. Common findings include:

- High white blood cell count, mostly lymphocytes

- Slightly raised protein levels

- Normal or low glucose

Though these results are not specific, they support the diagnosis if JEV antibodies or RNA are present.

Brain scans can also help. MRI often shows damage in areas like the thalamus, brainstem, or basal ganglia. CT scans may show swelling or localized damage. While not diagnostic, imaging helps rule out other diseases and supports clinical suspicion.

Excluding Other Illnesses

Many diseases mimic Japanese encephalitis. Doctors must rule out:

- Herpes virus brain infections

- Meningitis caused by bacteria like meningococcus

- Tuberculosis in the brain

- Dengue with brain symptoms

- Cerebral malaria

- Autoimmune brain disease

Comparing symptoms, lab data, and exposure helps doctors avoid misdiagnosis.

Reporting and Public Health Impact

Japanese encephalitis is often a notifiable disease. Confirmed cases must be reported to health authorities. This helps:

- Track outbreaks

- Measure vaccine success

- Launch mosquito control efforts

- Support health education

Public health labs confirm diagnoses and gather data to prevent future infections.

Conclusion

The diagnosis of Japanese encephalitis depends on careful evaluation of symptoms, history, and lab tests. Because the early signs are vague, doctors must stay alert—especially in unvaccinated patients returning from high-risk areas.

While tests like MAC-ELISA or PCR are key, the full picture—including brain scans and spinal fluid analysis—is essential. In areas with few resources, clinical signs and exposure history often guide the diagnosis.

Finding the illness early helps not only the patient but the wider community. Accurate and fast diagnosis supports public health goals, slows outbreaks, and strengthens vaccine efforts against this severe yet preventable disease.